A Hairstory of Texturism Continued...

Modern Overregulation, Reclamation, and Celebration of Afro Textured Hair

Picking up where we left off last time, we’ve arrived at the turn of the millennia!

THE NATURAL HAIR MOVEMENT 2.0

Good Hair

In the 2000s, the Natural Hair Movement saw its second wave since its emergence in the 60s.

Chanté Griffin discusses this second wave in her 2019 JSTOR scholarly article, How Natural Black Hair at Work Became a Civil Rights Issue;

“Spurred by films and the advent of social media, the movement fuelled a cultural shift that has caused legions of Black women to abandon their perms and pressing combs.

Director Regina Kimbell’s My Nappy Roots: A Journey Through Black Hair-itage traced the history and politics around natural Black hair in the U.S., thus raising consciousness in the African American community.

This was one year before comedian Chris Rock would release Good Hair a similarly themed documentary that focused on the economics of Black women buying weaves and perming their hair.”

Griffin continues discussing how while both films raised social consciousness, “YouTube and other social media platforms empowered these women to act on their new awareness. YouTube and natural hair blogs allowed Black women to discuss their hair-care journeys, share hair tutorials, and connect with other women.”

TODAY; THE EFFECTS OF COLONISATION

“Ungodly”

Southern Cross University Lecturer Dr Kathomi Gatwiri discusses the effects of colonisation today in her 2018 The Conversation article The Politics of Black Hair: An Australian Perspective;

“When I was growing up in a village in Kenya, we kept our hair short… We never questioned why we were not allowed to grow our hair; but at almost every school assembly, we were punished if we had not shaved our heads…

Author Dr Gatwiri as a child. Author provided

Revisiting that phase of my childhood now with fresh eyes reveals a problematic history. When colonial education started in Kenya, most schools were run by Christian missionaries who constructed a singular narrative about Black hair: that it was unsightly, ungodly and untameable.

They demanded that girls who attended their "godly" schools cut their hair to the scalp. Cutting girls' hair somehow minimised evidence of their womanhood. It was a covert move to reduce their desirability to African men, who were constructed as primal beasts with no sense of sexual control.

Artistic hairstyles were banned or criminalised in school and in church.

By enforcing these rules, the missionaries were able to successfully sexualise hair and use it as a tool of control and punishment in a way that Africans had never done.

Such historical understandings expose the political significance hair carries.”

She concludes her brilliant article by saying:

“Black hair is personal, but it is also political. It shows how Black consciousness and identities of race, gender and sexuality are constructed, reinforced and represented.”

TODAY; THE SOCIAL SITUATION

Unprofessional if you do, Unprofessional if you don’t

In 2016, The Perception Institute's “Good Hair" Study (the first study to examine implicit and explicit bias related to Black women’s hair) found that a majority of people, regardless of race and gender, hold some bias toward Women of Colour based on their hair.

A few years later, a 2020 Duke University study also found that Black women with natural hairstyles were perceived as less professional, less competent and were less likely to be recommended for job interviews than candidates with straight hair (who were viewed as more polished, refined and respectable).

This would elicit the biggest eye-roll ever if it wasn’t so incredibly concerning.

People with Afro textured hair face discrimination for wearing their natural hair texture, and for wearing hairstyles that are suitable and protective for their hair texture!

We still have issues with protective styles being labelled “ghetto” when worn on the hair texture they were invented for, but “trendy” and “innovative” when stolen by white people. Take the below comments by Fashion Police host Giuliana Rancic, for example;

Dr Kathomi Gatwiri also shared in her article that “Perhaps the most interesting aspect of growing hair that looks “different” in Australia is learning how to negotiate the constant attention it draws to me – from the unwarranted touch “just to feel my hair” to the unending questions about whether it is “real”…

The random and constant touching of my hair (and by extension my body) reveals how white privilege can function in hair politics. There is almost an unspoken expectation that Black hair should be available to the white audience as an object of curiosity through touching and interrogation of its authenticity.”

TODAY; THE LEGAL SITUATION

Where is our CROWN Act equivalent?

Following a slew of high-profile cases of hair discrimination, in 2019 the New York City Commission on Human Rights wrote:

“Bans or restrictions on natural hair or hairstyles associated with Black people are often rooted in white standards of appearance and perpetuate racist stereotypes that Black hairstyles are unprofessional. Such policies exacerbate anti-Black bias in employment, at school, while playing sports, and in other areas of daily living.”

Two months after NYC release its guidelines, California passed the CROWN Act, becoming the first state in the US to ban natural hair discrimination. Only 18 states have enacted this into law presently; The House of Representatives has passed the bill at the federal level, but it hasn’t been approved by the Senate yet.

The California law notes that “Professionalism was, and still is, closely linked to European features and mannerisms, which entails that those who do not naturally fall into Eurocentric norms must alter their appearances, sometimes drastically and permanently, in order to be deemed professional.”

So the USA has the CROWN Act, the UK has the Halo code…

Today in QLD, we have the 1991 Anti-Discrimination Act, but as of yet no states have passed legislation to protect against natural hair discrimination, or protective style discrimination. Queensland’s Human Rights Act of 2019 is meant to protect the distinct cultural rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, becoming the first state to specifically list this right in legislation…

And yet there have been countless instances of such discrimination in schools, the workplace, and in broader society.

So where is our CROWN Act / Halo code equivalent?

Diversity and Inclusion Manager Rebekah Gougeon in 2021 article, Black Hair is Never ‘Just Hair’: A Closer Look at Afro Discrimination in the Workplace, expresses:

“No one should be penalised for the way their hair grows out of their scalp or made to feel less than or othered. It is about freedom to wear your hair however you choose, whenever and wherever you want. Black hair is versatile, multi-faceted and deserves to be celebrated, in all its glory.”

So basically…

After our exploration through the centuries of discrimination against Afro textured hair, it’s pretty undeniable that texturism is an issue intrinsically rooted in racism. And like racism, it requires both legal and social change to abolish.

Dr Johanna Lukate speaks about how hair matters differently for Women of Colour in The Psychology of Black Hair, noting that “it’s about managing a marginalised identity…

While hair is a form of non verbal communication for all of us, Women of colour are having a different conversation;

For Women of Colour, hair is part of a conversation about the history of slavery and colonialism;

It is part of a conversation about the legacies of sexism and racism;

And it is part of a conversation about contemporary stories of migration and belonging.”

Stay tuned for the next edition of our Afro Hair series, where we discuss texturism within the Hair Industry today, and hear from some of our clients about their experiences with other afro hair salons!

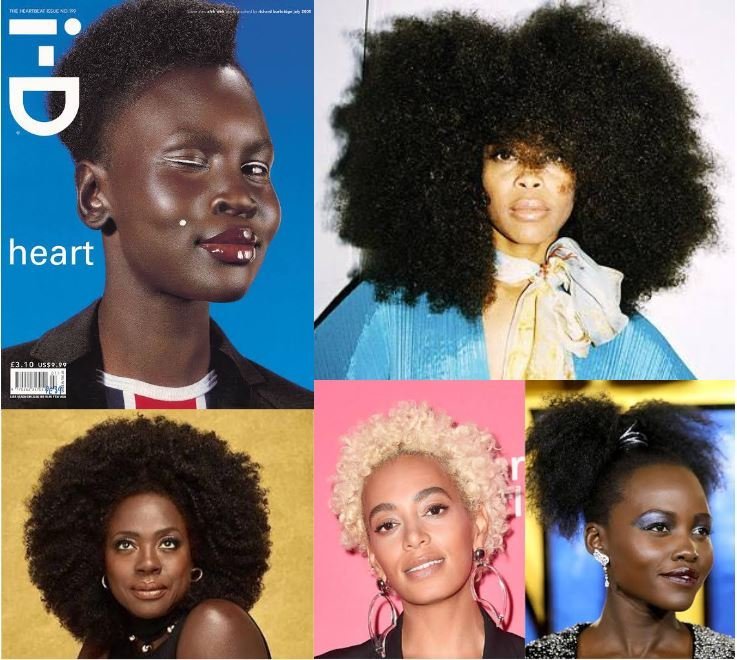

Black hair is beauty and versatility. Black hair tells the history of our heritage, it dictates the trends of today, and speaks to our resilience as Black people as we move towards the future. Black hair will continue to be a symbol of strength, illuminating our identities – however we choose to wear our crown.

– Celebrity hair stylist, Yene Damtew

RESOURCES:

Videos:

The Psychology of Black Hair |Dr Johanna Lukate | 2018 | TEDxCambridgeUniversity

Books:

Hair Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in America | Ayana D. Byrd, Lori L. Tharps | 2001

Hair Matters: Beauty, Power, and Black Women's Consciousness | Ingrid Banks | 2000

400 Years Without a Comb | Willie L. Morrow | 1973

Articles:

The Crown We Never Take Off: A History Of Black Hair Through The Ages | Quani Burnett | 2022

The Politics of Black Hair: An Australian Perspective | Dr Kathomi Gatwiri | 2018

Reclaiming our braids: Why is Black hair is still being politicised in 2021? | Sheilla Mamona | 2021

Black Hair' is Never 'Just Hair': A Closer Look at Afro Discrimination in the Workplace | Rebekah Gougeon | 2021

How Natural Black Hair at Work Became a Civil Rights Issue | Chanté Griffin | 2019

A History of African Women’s Hairstyles | Lebo Matshego | 2020

5 Ancient African hairstyles that are still popular today | Temi Iwalaiye | 2021

From Slavery to Colonialism and School Rules: a history of myths about black hair | Hlonipha Mokoena | 2016